Eight children in the UK have been spared from inherited genetic diseases thanks to a groundbreaking three-person in vitro fertilisation (IVF) technique.

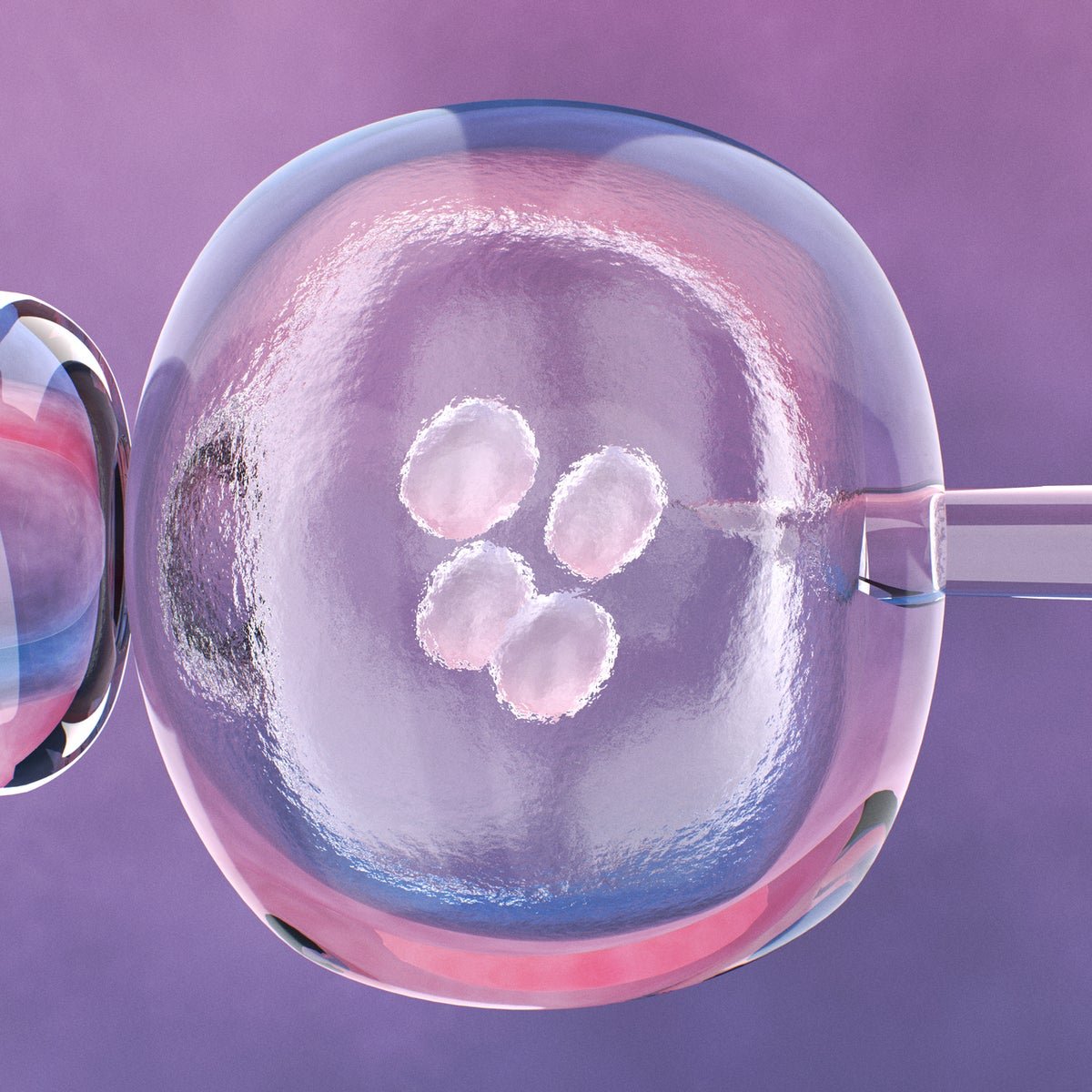

This innovative procedure, pioneered by scientists from Britain’s Newcastle University, involves transferring pieces from inside the mother’s fertilised egg, including its nucleus, plus the nucleus of the father’s sperm, into a healthy egg provided by an anonymous donor.

A Safe Haven from Genetic Disorders

The technique prevents the transfer of mutated genes from the mother’s mitochondria, which are the cells’ energy factories, that could cause incurable and potentially fatal disorders.

Mutations in mitochondrial DNA can affect multiple organs, particularly those that require high energy, such as the brain, liver, heart, muscles, and kidneys.

Healthy Babies Born Thanks to New Technique

One of the eight children is now two years old, two are between ages one and two, and five are babies. All were healthy at birth, with blood tests showing no or low levels of mitochondrial gene mutations.

All of the children have made normal developmental progress, which is a significant achievement according to the scientists.

A Decades-Long Effort to Develop New Technique

The successful results are the culmination of decades of work, not just on the scientific and technical challenges but also in ethical inquiry, public and patient engagement, law-making, drafting and execution of regulations, and establishing a system for monitoring and caring for the mothers and infants.

The researchers’ “treasure trove of data” is likely to be the starting point of new avenues of investigation, according to reproductive medicine specialist Andy Greenfield of the University of Oxford.

How the Technique Works

During IVF screening procedures, doctors can identify some low-risk eggs with very few mitochondrial gene mutations that are suitable for implantation. But sometimes, all of the eggs’ mitochondrial DNA carries mutations.

In those cases, using the new technique, the UK doctors first fertilise the mother’s egg with the father’s sperm. Then, they remove the fertilised egg’s “pronuclei” – that is, the nuclei of the egg and the sperm, which carry the DNA instructions from both parents for the baby’s development, survival, and reproduction.

Next, they transfer the egg and sperm nuclei into a donated fertilised egg that has had its pronuclei removed.

The donor egg will now begin to divide and develop with its healthy mitochondria and the nuclear DNA from the mother’s egg and the father’s sperm.

This process essentially replaces the faulty mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) with healthy mtDNA from the donor, senior researcher Mary Herbert, professor of reproductive biology at Newcastle, explained.

Blood levels of mtDNA mutations were 95 per cent to 100 per cent lower in six newborns, and 77 per cent to 88 per cent lower in two others, compared to levels of the same variants in their mothers, the researchers reported.