Tick-Bite Epidemic: The Chronic Illness That’s Leaving Thousands of Australians in Agony

- Thousands of Australians are suffering from chronic symptoms after tick bites, with many forced to spend thousands on unproven tests and treatments.

- Researchers are still in the dark about the cause of the illness, known as DSCATT, and how to best treat it.

- A Senate inquiry has found that patients are struggling to access care and are often dismissed by doctors, leaving them feeling “believed” and “seen”.

In the quiet suburbs of northern Sydney, retired GP Dr Richard Schloeffel has seen it all. Over three decades, he treated thousands of patients with complex chronic diseases, from myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) to long COVID. But it was a group of patients with debilitating, ongoing symptoms linked to tick bites that prompted him to take a closer look.

“I think tick-borne illness can be treated,” Dr Schloeffel, now a researcher at Macquarie University, said. “It’s just that you have to believe the patient is sick in the first place.”

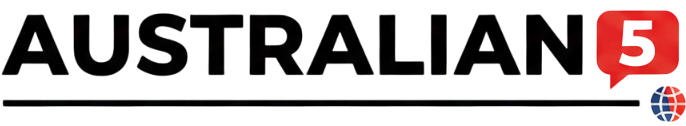

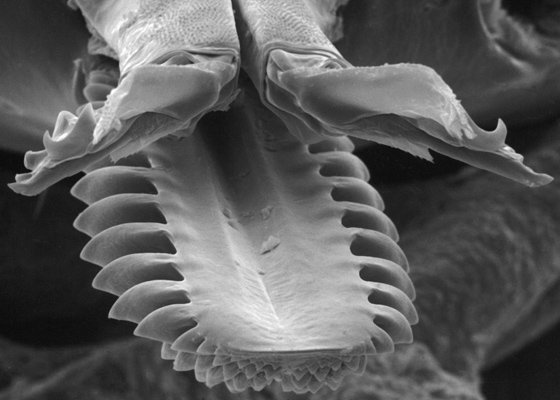

These patients, suffering from what’s known as DSCATT (debilitating symptom complexes attributed to ticks), report persistent symptoms including fatigue, joint pain, and neurological problems. But despite the severity of their illness, many are forced to navigate a healthcare system that’s often sceptical of their claims.

“Most people in Australia who get a tick bite don’t get sick. We’re talking about the tip of the iceberg,” Dr Schloeffel said. “But for those who do report illness, many struggle to feel believed or seen.”

In fact, a Senate inquiry earlier this year found that many patients were spending thousands of dollars on unproven testing and treatment, often with little success. “People bankrupt themselves to find treatment and get diagnosed,” Dr Schloeffel said.

So what’s going on? Scientists are still in the dark about the cause of DSCATT, and how to best treat it. While some researchers are exploring the possibility of infection-induced immune dysfunction and chronic inflammation inside cells, others are investigating the benefits of psychological therapy.

One such study, led by Professor Richard Kanaan at the University of Melbourne, is exploring whether a psychology-based intervention can help people with DSCATT manage their illness. “We’re not necessarily talking about a cure, because people … may go on having the illness,” Professor Kanaan said. “But we’re talking about improvement.”

But the research is slow going, and patients are growing frustrated. “Why psychiatry is involved is because understanding a complex problem – it needs a holistic approach,” Professor Kanaan said. “As much as we’d like there to be a very simple explanation … it doesn’t seem to be that kind of problem.”

In the meantime, patients are left to suffer in silence, their illness dismissed as “the tip of the iceberg” of tick-borne diseases. It’s a frustrating, debilitating, and often devastating reality – and one that demands more attention, more funding, and more compassion.