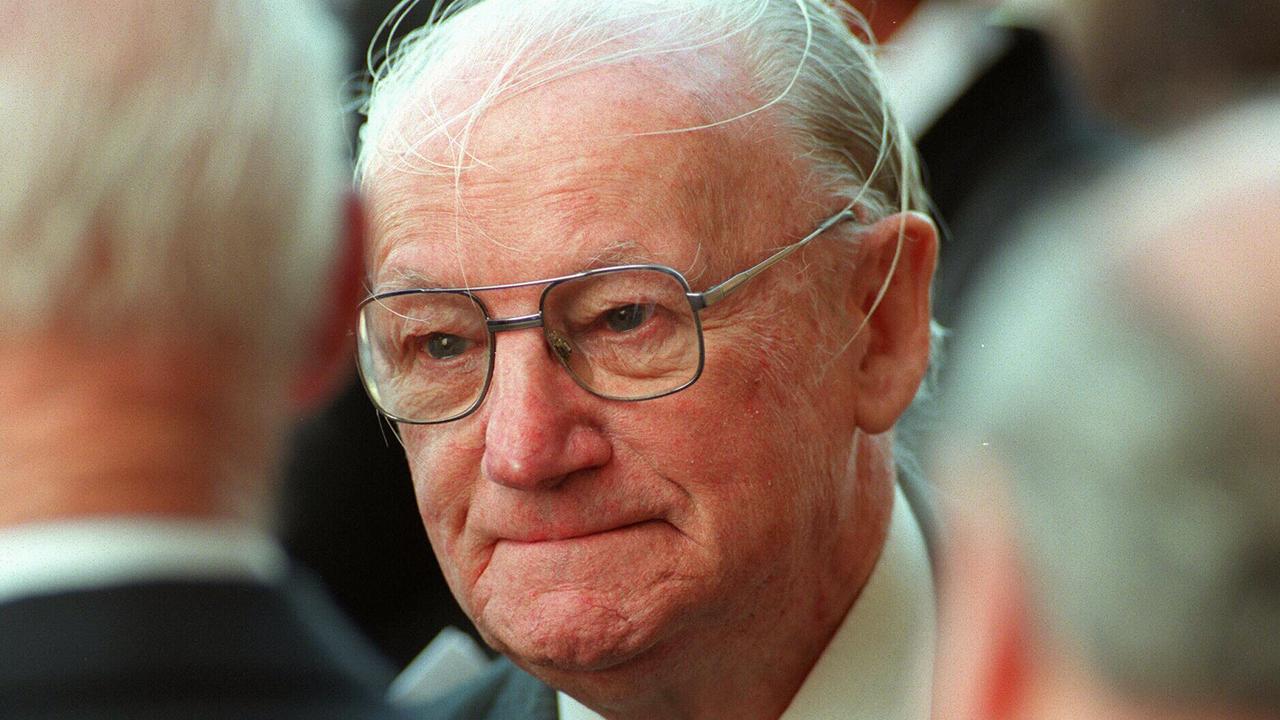

Deep within the National Library of Australia lies a treasure trove of letters written by the cricketing legend, Sir Donald Bradman, between 1984 and 1998.

These 20 letters, donated by the family of his English friend, Peter Brough, offer a fascinating glimpse into Bradman’s thoughts on cricket, politics, and fame.

As we dive into the contents of these letters, we discover a side of Bradman that was previously unknown, revealing his admiration for Shane Warne, his identification of a young Ricky Ponting, and his fears of a second World Series Cricket.

The Rebel Tours and the Fears of a Second WSC

In 1985, Bradman penned a letter to Brough, expressing his concerns about the state of cricket following the rebel tours to South Africa. At the time, international cricket was in disarray, with players being lured by lucrative offers to play in South Africa, despite the apartheid regime. Bradman worried that this could lead to a second World Series Cricket, which he vehemently opposed.

“I don’t blame the players,” Bradman wrote. “One I know has been out of work for two years, and to see a fair offer of $200,000 for two years was too good to turn down. Of course, the whole thing hinges on dirty rotten politics.”

A Cricketing Icon’s Take on Shane Warne

Fast-forward to 1993, and Bradman was singing the praises of a young Shane Warne, who had just burst onto the cricketing scene. “But thankfully we may at last have produced a good leg spinner in young Warne,” Bradman wrote. “He’s only 23 and really spins the ball. I am impressed by his accuracy.”

Bradman’s admiration for Warne only grew stronger over the years. In 1994, he wrote, “Shane Warne is bowling brilliantly and causing all sorts of trouble… Excepting Bill O’Reilly, Warne is the best slow leg-spinner we’ve produced, better even than Clarrie Grimmett, and that is very high praise.”

Spotting Young Talent

Bradman’s keen eye for talent extended beyond Warne. In 1986, he identified a young Steve Waugh as a “class bat,” and three years later, he was impressed by a young Darren Lehmann. “Just before becoming ill I went to cricket one day and saw a youngster (19) named Lehmann make 228 v NSW,” Bradman wrote. “It was his first century – he followed it with 86 versus New Zealand yesterday and looks like a possible selection, a left-hander in the mould of Neil Harvey but a bit more stocky as yet more risky.”

In 1995, Bradman was keeping a close eye on the one-day domestic competition and was thrilled to see a young Ricky Ponting from Tasmania. “Young Ponting of Tasmania played a beautiful innings here yesterday and looks a Test prospect,” he wrote.

Fame and the Price of Success

Despite being a cricketing icon, Bradman never enjoyed the attention that came with fame. In 1985, he wrote, “The publicity, the functions… being on display… is not my idea of enjoyment.” In 1998, after his wife Jessie passed away, Bradman found it difficult to cope with the loneliness and the constant attention. “I am struggling to get on with life, but wherever I turn there is sadness and memories,” he wrote.

A Life Dedicated to Cricket

Through it all, Bradman remained dedicated to the sport he loved. In 1997, he wrote, “I don’t go to cricket anymore – I can no longer tolerate the press, TV or autograph hunters who won’t leave me alone when I appear in public, so really I am living the life of a recluse.” Yet, he continued to follow the game, offering his insights and opinions to Brough.

These letters offer a unique glimpse into the life and mind of Sir Donald Bradman, revealing a complex and multifaceted individual who was not only a cricketing legend but also a humble and private person. As we delve into the contents of these letters, we are reminded of the importance of preserving our sporting heritage and the valuable lessons that can be learned from the past.